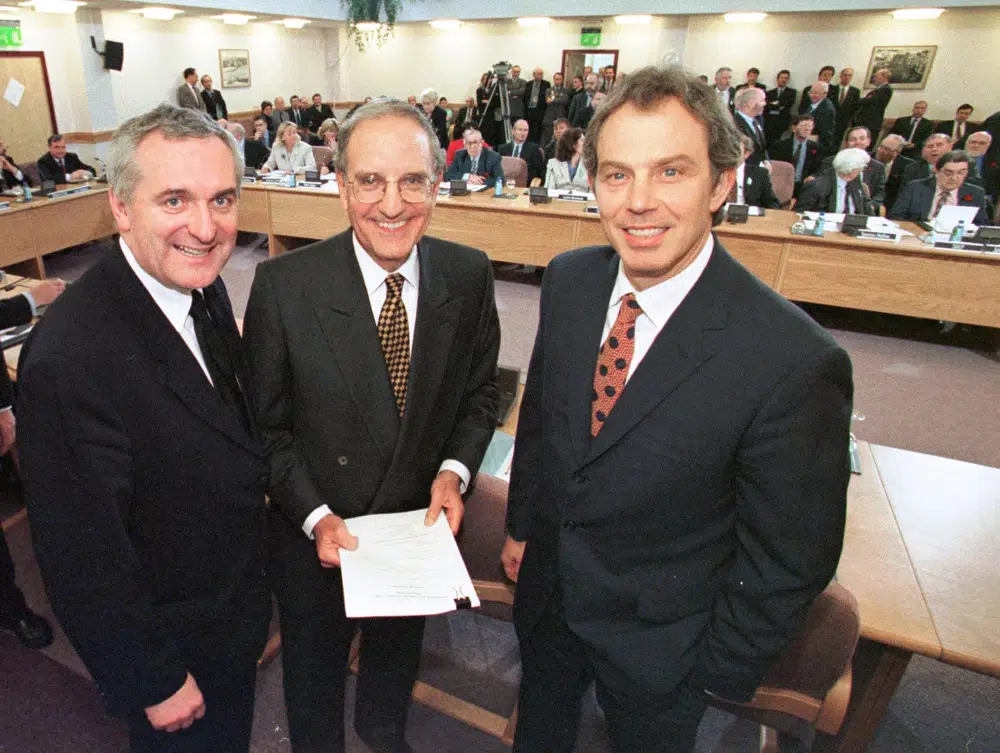

From right, British Prime Minister Tony Blair, U.S. Sen. George Mitchell, and Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern, pose together after they signed the Good Friday Agreement for peace in Northern Ireland, on April 10, 1998. It has been 25 years since the striking of the Good Friday Agreement, the landmark peace accord that ended three decades of violence in Northern Ireland, a period known as “the Troubles.” (AP Photo, File)

When Ireland, long dominated by its bigger neighbor Britain, became a self-governing Roman Catholic-majority country a century ago, a six-county region in the north with a Protestant majority remained part of the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland was split between two main communities: nationalists — most of them Catholic — who desired union with the rest of Ireland, and largely Protestant unionists, who wanted to stay British. The Catholic minority experienced discrimination in jobs, housing and other areas in the Protestant-dominated state. In the 1960s, a Catholic civil rights movement demanded change, but faced a harsh response from the government and police.

The situation deteriorated into a conflict involving Irish republican militants, loyalist paramilitaries and U.K. troops. Bombings and shootings killed some 3,600 people, mostly in Northern Ireland, though republicans also set off bombs in mainland Britain. By the early 1990s, the armed conflict had reached “a hurting stalemate,” said Katy Hayward, professor of political sociology at Queens University Belfast. “There was a recognition on the part of the British government and army, and on the Irish republican side as well, that there was never going to be an outright victory.” The Irish Republican Army called a cease-fire in 1994, allowing its allied party, Sinn Fein, to join other nationalist and unionist parties in peace talks co-sponsored by the British and Irish governments. The United States played a key role — former Sen. George Mitchell chaired the talks, spending 22 months in Belfast overseeing the delicate multi-party negotiations. The talks came close to collapse several times. But after a marathon weeklong negotiating session that stretched long past deadline, agreement was reached on April 10, 1998 — Good Friday. British Prime Minister Tony Blair hailed the agreement, saying: “Today I hope that the burden of history can at long last start to be lifted from our shoulders.” The following month, the agreement was ratified by voters in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The agreement gave formal recognition to Northern Ireland’s multiple identities, allowing residents to identify as British, Irish or both. It ended direct U.K. rule and set up a Northern Ireland legislature and government with power shared between unionist and nationalist parties. The agreement affirmed Northern Ireland as part of the U.K. but set out that it could in future unite with Ireland if a majority in both the north and the republic supported the move. After some hiccups, militant groups agreed to disarm, and paramilitary prisoners jailed for taking part in the violence were freed — something that remains a sore point with victims and bereaved families. The British military withdrew and dismantled its bases and border checkpoints. People and goods could flow freely across the all-but-invisible border between Northern Ireland and the republic. The peace has held.

Trade between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was straightforward until Great Britain including Northern Ireland left the European Union (EU), a deal was required to allow trade to continue across the border. The EU has strict food rules and requires border checks when certain goods – such as milk and eggs – arrive from non-EU countries like the UK. Paperwork is also required for other goods. But the idea of checks at the border with Ireland is a sensitive issue because of Northern Ireland’s troubled political history. It was feared that introducing cameras or border posts as part of checks on incoming and outgoing goods could lead to instability.

Former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson agreed that a Northern Ireland Protocol with the EU was needed. It became part of international law and was put into effect on 1 January 2021. Under the Northern Ireland Protocol, new checks were introduced. But rather than taking place at the Irish border, inspection and document checks are carried out at Northern Ireland’s ports. This applies to goods travelling from Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) to Northern Ireland.

The checks apply even if the goods are due to remain in Northern Ireland. The deal was approved by the UK Parliament, and formally adopted by the UK and the EU. However, Northern Ireland’s largest unionist party, the Democratic Unionist Party voted against it and is still refusing to take part in Northern Ireland’s power-sharing government until its concerns are addressed.